The Limits of Your Liberty

If you’re reading this, then you’ve already heard the news. On Monday, the Supreme Court decided another in a long line of cases involving the battle over abortion rights in America. And for the second time in as many weeks, Chief Justice John Roberts, head of the Court’s conservative wing, joined the four liberal Justices in an opinion that looks very anti-conservative to many observers.

You know me by now. You know what this blog is all about. You know I don’t care about labels like “liberal” or “conservative,” and I certainly don’t think those notions have a place on the Supreme Court. What I care about is telling you what you need to know about the facts and the law in the most impartial way possible, so that you can go out and talk circles around your friends when they try to bring up the most recent Supreme Court decision. So check your prejudices and your political opinions at the door and let’s talk about abortion.

We’ll start with the basics.

Background

As you undoubtedly know by now, in America, a woman has a fundamental constitutional right to have an abortion. That rule comes from a very famous 1973 case called Roe v. Wade, which is all the rage these days. I could go on for days about Roe v. Wade, but you have places to go and people to see, so I’ll restrain myself. That said, there are a few things we need to be clear on.

First, just because Roe made abortion a fundamental right, doesn’t mean it made that right absolute. Instead, a woman’s right to an abortion is qualified, like most other constitutional rights, and can be limited by the government in certain situations. So, of course, the question in the years following Roe was what sorts of limitations on the right to abortion are appropriate. In 1992, the Supreme Court answered that question in a case called Planned Parenthood v. Casey. That case essentially held that any government restriction that created an undue burden on the right to an abortion was unconstitutional. What is an undue burden? Well, that depends on the facts of each particular case. We’ll talk more about that in a bit. Today, when abortion cases are decided, they’re generally decided based on the holding in Casey, not the holding in Roe.

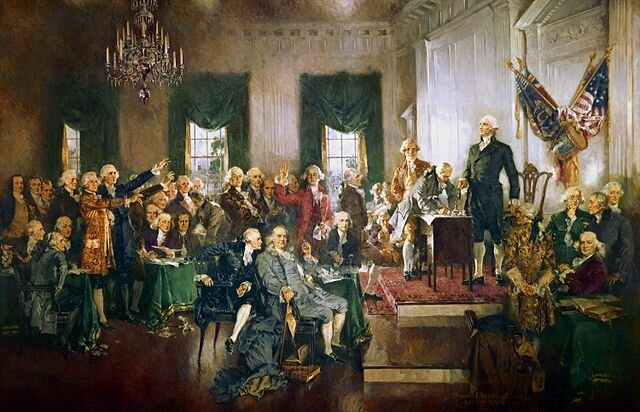

Second, the right to have an abortion is different from other constitutional rights in that it does not come directly from the text of the Constitution. What I mean is that unlike, for example, the right to freedom of speech, which is spelled out explicitly in the First Amendment, the right to have an abortion does not appear directly in the Constitution. And that makes sense, right? The fuzzy old white guys that wrote the Constitution were not concerned with a woman’s right to control her body. Most of them thought of women as objects. Many of them owned slaves.

The fuzzy old white guys who wrote the Constitution

So if the right to have an abortion doesn’t appear in the Constitution, where did it come from?

Well, it comes from the Fourteenth Amendment, via something called substantive due process. That’s a complicated legal principle and I don’t want to get too far into the weeds on it right now, but let’s give it a brief definition, shall we? The Fourteenth Amendment, which was passed in 1868, after the Civil War, was initially intended to provide freed slaves with due process and the equal protection of the law, which they were not getting in the Reconstruction South. When you hear people talk about the Due Process Clause or the Equal Protection Clause, either they’re talking about the Fourteenth Amendment or they don’t know what they’re talking about and they’re just hoping it sounds intelligent. But anyway, in the early/mid 1900s, lawyers and legal scholars began arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment did more than just protect freed slaves or racial/ethnic minorities. Instead, they began to argue that the Due Process Clause actually contained its own set of fundamental rights that were protected from government intervention. Let’s take a look at the Due Process Clause to see how that works:

“No State shall ... deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”

The substantive due process argument goes something like this: the “liberty” described by the Due Process Clause includes more than just physical freedom. It also includes many other freedoms fundamental to human existence. In fact, it includes a whole list of these fundamental freedoms, or fundamental rights, just waiting to be discovered and protected against government intrusion. It might come as a surprise to hear that for many years, the Supreme Court bought that argument. It used substantive due process to create a whole slew of new fundamental rights, including the right to freedom of contract, the right to raise children, and, most importantly, the right to privacy. None of these rights was mentioned explicitly in the Constitution, and yet the Supreme Court read the Due Process Clause to include all of them, if not directly, then by implication.

However, substantive due process is not the juggernaut it once was. The Court these days is much more hesitant to recognize new fundamental rights than it might have been last century, even going so far as to decline to recognize a fundamental right to choose the manner of one’s death. But, that said, that hasn’t stopped the existing fundamental rights from being used in new ways. The right to privacy is the most powerful of these rights, and has been used to strike down laws involving everything from contraceptives to gay marriage. And it was this right to privacy that ultimately created the fundamental abortion right in Roe v. Wade.

Now, if you’re familiar with the blog, you can probably already see where the conflict comes in. As we’ve discussed, the conservative wing of the modern Supreme Court tends to follow a theory of legal interpretation called textualism. Generally, the Court’s conservatives believe that the most important consideration in interpreting any law is the intent and understanding that would have existed among the people that wrote the law. You can probably see how someone who thinks this way might have a problem with substantive due process. Their view is generally that the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Constitution as a whole, can’t protect something like abortion (or any of the substantive due process rights) because the Founding Fathers and the people who wrote the Fourteenth Amendment couldn’t possibly have had any of that in mind when drafting the law.

So that’s the backdrop. Now let’s talk about the case.

Unlike some of our other cases, the facts at issue here aren’t really that important. That’s because the facts and the law at issue are almost identical to the facts of a case decided in a 2016 case called Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt. Let’s just say that in that case, as in this one, a state (in that case Texas, in this case Louisiana) imposed a series of limitations on the clinics that were permitted to perform abortions in that state. Most relevant among these restrictions was the rule that each clinic seeking to perform abortions needed to have admitting privileges at a local hospital. These privileges were very difficult to obtain and had the practical effect of limiting the number of Texas abortion clinics in Hellerstedt by more than half. The Supreme Court, relying on the rule in Casey, determined that these restrictions were unnecessary, and that they imposed an undue burden on the abortion right.

And in this case, the law being challenged in Louisiana is so similar that the majority calls it “almost word-for-word identical.” That said, you would probably expect the result in this case to be the same, and of course, it is. But why? Well, essentially because of something called stare decisis. Stare decisis is a shortened form of the Latin maxim stare decisis et non quieta movere, which means, basically “to stand by decisions and not disturb the undisturbed.” What it means, legally-speaking, is that the Court (or any court, really) is supposed to stick to its prior decisions (or precedents) when confronted with a similar factual scenario. The general idea is to create stability and confidence in the legal system, and to produce predictable outcomes. And in this case, the majority opinion is based on the idea that prior case law—Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt—required this outcome.

That makes some sense right? If the Court decided a case four years ago with the exact same set of facts, we would assume—maybe even expect—that the result would come out the same, even if the composition of the Court has changed in the meantime. I mean, let’s think about what the alternative would be. Imagine, for a moment, that this case had turned out differently. Imagine that despite the fact that the law here is “almost word-for-word identical” to the law in Hellerstedt, the Court comes down a different way. What kind of assumption would you make about the Court if that happened? You’d probably assume that it was political, right? That the Court had changed its mind not because of the facts or law but because its political alignment had shifted over the last four years. Now, depending on how you feel about abortion, that would either delight or infuriate you (this is America, there’s no middle ground). But I’m going to suggest that no matter how you feel about abortion, it should frighten you. If the Supreme Court can change the law around every few years when new Justices arrive and old ones depart, how much confidence are we going to have in the law? How much are any of us going to be able to trust the Court and the decisions that it makes? Not very much, I’d suggest. And stare decisis essentially exists to prevent that from happening.

Chief Justice John Roberts, who this term has become the swing vote on several high-profile cases, including this one.

Now, if there’s anyone who cares about preserving the legitimacy of the Court, and enhancing our faith in its decisions, that person is John Roberts, who, as Chief Justice, is responsible for those sorts of things. That goes a long way to explaining why Chief Justice Roberts might join the liberal Justices in striking down the Louisiana law, doesn’t it? He wants his Court to be stable, predictable, and appear free from any political manipulation. If he were to decide this case differently than Hellerstedt, it would almost-certainly create the impression that he was allowing his own political beliefs to influence the Court.

And before you question that conclusion, I should mention that Chief Justice Roberts also wrote a concurring opinion in this case, in which he said this:

“I joined the dissent in [Hellerstedt] and continue to believe that the case was wrongly decided. The question today however is not whether [Hellerstedt] was right or wrong, but whether to adhere to it in deciding the present case.”

What does that mean? Well, first of all, it means that stare decisis was indeed the deciding factor in this case. It also means though, that Chief Justice Roberts may not be a supporter of abortion rights in future cases. What he’s telling you there—and what he goes on to suggest throughout his opinion—is that this case would have been decided differently if not for Hellerstedt, and also that future state laws limiting abortion may meet with more tolerance on the Supreme Court, just as long as they aren’t identical to laws that have already been invalidated.

That’s all important to understand, now and in future cases. But let’s move on and talk about the dissents.

If the majority opinion was about bringing this case in line with Hellerstedt so that stare decisis would apply, most of the dissents are about highlighting the ways in which this case differs from Hellerstedt.

Now, of course, abortion is a controversial issue, and so are the cases interpreting it. As such, it probably won’t surprise you to find out that each of the four conservative Justices wrote his own dissent in this case. In the interest of time, I’m going to divide those dissents into two groups: the dissents involving factual issues (Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, and Alito) and the dissent involving legal issues (Thomas).

As to the first category, suffice it to say that Justices Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, and Alito do not believe that the Louisiana law at issue in this case is “word-for-word identical” with the law in Hellerstedt. In fact, their opinion is that the law is different enough that Hellerstedt should not control the outcome. Now, that’s an interesting factual question, but it requires a thorough analysis of a whole range of factors, including things like the safety and cleanliness of abortion clinics, the history of Louisiana laws governing physicians, and the relative standard of medical care provided by both clinics and hospitals. If I go through all of it, we’ll be here all month. That said, I do recommend checking out the opinion using the link above if you’re interested.

That sort of rigorous inquiry is very different from the approach proposed by Justice Thomas, who doesn’t care about the factual argument because he believes that Roe and Casey were wrongly decided and should be overturned. As we’ve already discussed, Justice Thomas is a textualist, and accordingly, he believes that any supposed fundamental right that doesn’t exist in the text of the Constitution (such as the right to privacy, the right to marriage, and the right to abortion, among others) isn’t really a right at all and shouldn’t be protected from state intervention.

Justice Clarence Thomas

But what about stare decisis? Isn’t Justice Thomas bound by the prior decisions on abortion? Well, yes and no. You see, stare decisis is a flexible rule. Most of the time, it makes Supreme Court decisions very difficult to overrule, but it isn’t insurmountable. The Supreme Court has overturned its own precedents on countless occasions, most commonly when reaches a consensus that those precedents are unnecessary or were wrongly decided. Justice Thomas is arguing the latter, and he’s been arguing it for decades now. The really interesting thing is that in this case, the State of Louisiana never even argued that Roe and Casey were wrongly decided. Justice Thomas brought it up of his own accord, and he was the only one of the Justices to do so. That, of course, tells you how he feels, not only about Roe and Casey, but also about all the other fundamental rights cases.

So where does that leave us now?

Well, pretty much right where we started. The Louisiana law in this case is unconstitutional, but other than that, nothing much has changed, at least on the surface.

But let’s look a little bit deeper and consider what this decision means. It’s worth asking, would things have looked differently if the facts in this case hadn’t been so similar to Hellerstedt? Without stare decisis to fall back on, would Chief Justice Roberts have voted differently? The answer is almost certainly yes. But as to how the opinion might have changed, no one can really know for sure. That said, Chief Justice Roberts wrote some things in his concurring opinion that have led legal scholars to think he might be open to revisiting the issue with a less restrictive abortion law. And he’s pretty much the swing vote on the issue, as he so often seems to be these days. The other eight Justices have all staked out their positions on this issue, so we may now be in another holding pattern, waiting to see if another state wants to push the envelope on abortion.

That will undoubtedly happen, as it has so many times in the years since Roe, but by the time it does, the Court may look completely different. Until then, we should all do our best to respect the people on both sides of this issue, to listen to what they have to say, and to allow them to give voice to their opinions. As always, that’s what the law is all about.

Takeaways:

Ok, in conclusion, let’s summarize the case and give you some talking points to use on that one friend who thinks he/she is smarter than you.

This case isn’t really about abortion in a general sense—it’s really about stare decisis, and how much the Court is concerned with sticking it its precedents.

Stare decisis is a legal principle that essentially requires courts to stick to their prior decisions when similar cases arise. It exists to create stability and legitimacy in the legal system and to produce predictable results.

Consider what might happen in a world without stare decisis. Would you have faith in a legal system that revisited its precedents each time the political alignment of the Supreme Court changed?

In this case, the appropriate precedent is not Roe but rather Casey, the case which established the undue burden standard for abortion rights.

Chief Justice Roberts joined the four liberal justices in this case, out of an admitted desire to adhere to promote the legitimacy of the Court and to dispel any argument that the Court is susceptible to political pressure.

The right to an abortion does not exist in the text of the Constitution. Instead, it comes from a right to privacy that the Supreme Court found implied in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This is called substantive due process.

Substantive due process is no longer in favor on the Supreme Court, which is now much more hesitant to recognize new fundamental rights.

Stare decisis compelled the result in this case, but it is not insurmountable. The Supreme Court can still decide in future that its past precedents were wrongly decided.

That’s all for this week.

As always, don’t forget to stay up to date by following the blog on social media using the links above, and feel free to contact me directly via the Contact page with all your comments, concerns, and unsolicited political opinions. You can also sign up for the Impartial Review Newsletter using the link on the Contact page.